The Worldview Series

A series of articles with Baptist News Global introducing the hypothesis of the book, Worldview Theory, Whiteness, and the Future of Evangelical Faith, listed here in order of publication.

What if your ‘Christian worldview’ is based on some sinful ideas?

I suspect that few people who frame their ideas, or their disagreements with others, in terms of “worldviews” have felt the need to deliberate on what that word means, let alone whether it is valuable or valid. Few, that is, outside the evangelical circles that have labored to develop this sensibility in churches and schools over the last many years. This notion has a common-sense appeal and authority in 21st-century American life. Worldviews or world visions have become increasingly necessary in naming and talking about the many ways people see, reason about and live within our highly connected, densely diverse world.

A short history of the roots of colonialism, racism and whiteness in ‘Christian worldview’

The state of the conversation around race in many corners of America, including too many churches, is a mess. And before we get too far down the road, I want to register my hesitation about trying to abridge what I argue with greater care and detail in my book. Wading into the borderlands of critical race studies is perilous, especially in a social climate where even the mention of terms such as “whiteness” is a nonstarter. My hope is to join or open a genuine, searching conversation, not shut down the very possibility. But I have seen enough to know how tough that needle is to thread — not least when one must start with an article title provocative enough to grab attention.

Putting the white in witness since the 1940s

Now is the time to bring our conversation about whiteness and world-viewing into the present tense. The language and concept of worldviews are somewhat clear in many corners of evangelicalism today, but how does whiteness figure into these concepts? And to what degree could this possibly be a problem among the everyday faithful? We may well acknowledge some of the historical problems (like Kuyper’s arguments around race and colony) without really thinking that the very form for thought established in those days could itself be a problem. Looking ahead, I acknowledge this is tough work, hard to do well in a short space, and requires good-faith effort from both writer and readers.

Why your worldview might be both more and less than biblical

Today, I will work to read psychology and Christian ethics together to explore why it feels right to think of ourselves as common-sensical, biblical world-viewers — and how that self-conception misses the mark of the kind of creatures we are. Thus far in this series, I have largely analyzed worldview theory as it emerged in history. What follows has its historical elements but will begin to drive my criticism deeper into the posture and structure of “world-viewing” as it shapes our lives today. The worldview concept and its underlying impulse, as we already have seen, can allow troubling practices and convictions — biases, bigotry and otherwise bad ideas — to evade and even resist transformation in a Christian’s mind.

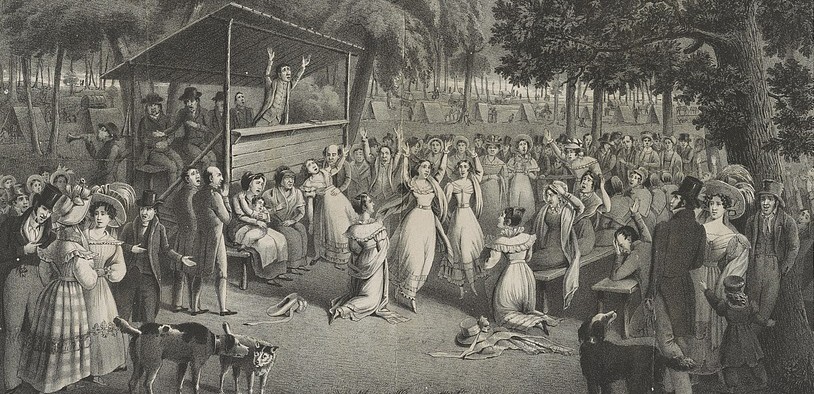

Who needs the church when we have the biblical worldview?

After his second visit to New York in 1939, Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrestled with the character of Protestant churches in America versus those in Europe in an essay titled “Protestantism without Reformation.” Even as he introduced his argument, which plays up history, sociology and political analysis for understanding the American church, Bonhoeffer offered some words of caution about using these modes. He expressed concern about balkanizing the global church, failing to see the single, shared office of God’s church in the world, and neglecting the real value of concrete church-communities that differ from our own. And I share these concerns.

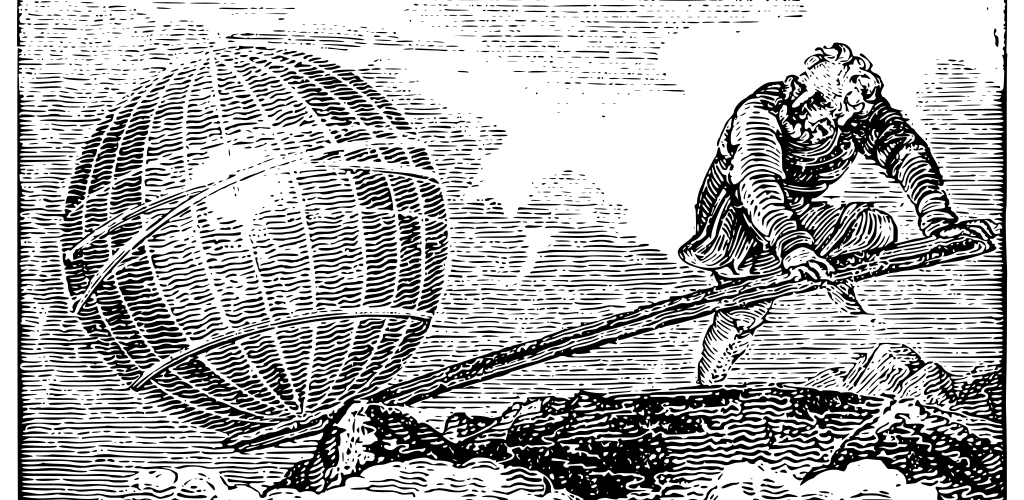

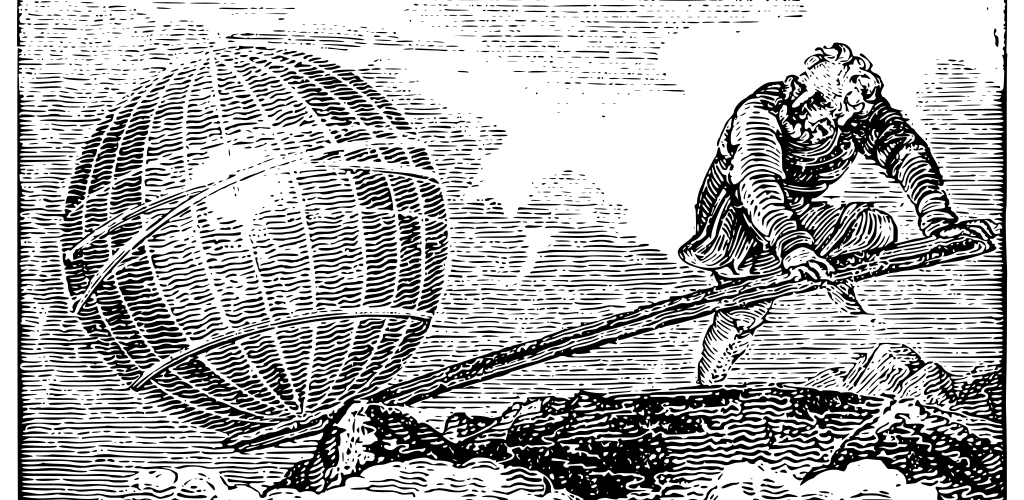

Was Adam and Eve’s ‘worldview’ the original sin?

Snowed in with my family over the Martin Luther King Jr. Day of Service, I stole a few moments away to read and reflect on racism in American society, how it persists even as its forms change, and ways to participate in its undoing. Like so many inspirational figures in human history, King’s message and memory have been grasped and used in numerous ways, toward many ends, by a fairly surprising variety of people. Everyone likes to have a little MLK in their pocket, to think of themselves as defending his legacy. But I must confess that my mind drifted from King toward another great American crafter of words and social critic, James Baldwin. Setting out to read his essay titled “Nothing Personal,” I found a particular thread tangling me up.