Articles

Pulling back the curtain

Around the dinner table recently, my family of five discussed our favorite season of the year. Two preferred the coziness of fall, one winter’s crispness with Christmas delights, two the summer’s change of pace and lengthened daylight.

I have noticed that individual believers and whole church communities tend to build their morals upon one key biblical season. Each shapes one’s imagination of what God’s peace is and how and when it comes to us.

This article invites us to reimagine God’s peaceable reign—not as a timeline, but as a multiverse of divine possibility. As we embody God’s peace, we open portals to a reality truer, better, and more beautiful than the one we see each day.

Developing the skill (and will) for navigating everyday conflicts

Rev. Dr. Jacob Cook challenges church communities to accept conflict as an everyday part of living in community with other imperfect people and use it as a constructive force.

For local churches, the relational condition for creative conflict may be the most abundant. What keeps people together, we might say, “despite their differences,” is a shared history with and appreciation for this community. And it’s relatively easy to imagine why, when the conversational waters get choppy with distress, unkindness and, especially, harm, a church-community might call upon outside professionals to bring their skills and deploy a structured process to help the relationships survive through conflict, and even thrive afterward.

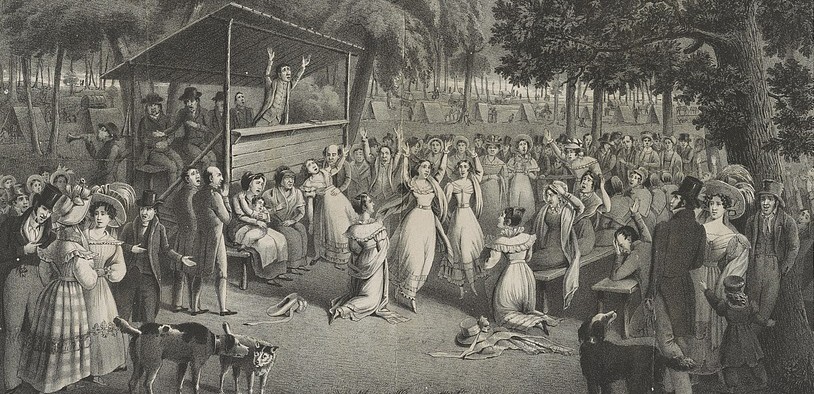

A new fundamentalism rising: The Southern Baptist Battle against the CRT “worldview”

This article focuses on figures in the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) reacting against “Critical Race Theory,” “Intersectionality,” and American cultural discourse more broadly. It situates this reaction within the tradition of American Fundamentalist Christianity and the rise of Neo- Evangelicalism starting in the 1940s, particularly this tradition’s resistance to critical theories and its use of “worldview theory” as a rhetorical framework in support of false-conservative sociopolitical policies (e.g., defending race, gender, and sexual essentialisms). This article argues that SBC figures’ attack on CRT/I not only lacks intellectual rigor but also, perhaps more significantly, is inspired largely by cultural forces and political sources despite their rhetorical insistence upon the authority of the Bible alone, uninterpreted by traditions. It positions the SBC’s rejection of CRT (and earlier cognates) as a kind of new Fundamentalism that is continuous with earlier forms both in terms of the underlying theology and the rhetorical expression that are naturalized within EWT. This article ends by suggesting how the debates around CRT provide a rhetorical model for right-wing Christian discourse around “religious freedom” in public schools.

Teaching AI about Ethics and the Gospel

Can we train artificial intelligence to coach us into deeper honesty so we can help others — whose lives it might know more intimately than we do?

As we enter this new territory, we would do well to reflect critically about how to direct and interact with AI technologies, now and in the future. As much as this aim sounds like science fiction, it is also the work of Christian ethics. Readers already know the challenges of human moral formation, whether inside or outside the church. But let us consider the other side with a healthy appreciation for the imaginative thinking that sci-fi inspires. What might we teach to artificial general intelligence (or “strong AI”) as the stuff of “ethics”? What could we form AI to follow with religious devotion? And how?

Review of Pamela Cooper-White’s The Psychology of Christian Nationalism

By January 2021, we had already witnessed the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville and starkly lopsided responses from law enforcement to #BlackLivesMatter protests in the wake of George Floyd’s 2020 murder. We were already dealing with loved ones drawn into the QAnon whirlpool, urging us to wake up and #savethechildren. Nevertheless, for many of us glued to our screens on January 6, mouths agape at the scenes unfolding before our eyes, the events of that day crystalized the sense that in the fever pitch of American social discourse, with all the vitriol and conspiracy and alternate truths of recent years, we stand as vulnerable as ever to domestic terrorism, authoritarian coercion, and political violence. For Christians who find these developments troubling—not least given the involvement of so many who nominally profess the same religion—numerous questions too often press into even intimate spaces, like dinner tables and Sunday school classrooms: What is the source of these emotions, ideas, and actions? Why are people drawn into this mess? And how can we even begin to talk across this divide? This book presents Cooper-White’s response to these questions against the widely discussed backdrop of “Christian nationalism.”

Want diversity? Look beyond your walls

Across the United States, churches have set up book studies and workshops to better understand the history of racism, current racial injustice and the effects of whiteness on how they see the world. As I have interviewed pastors and laypeople navigating these waters, many have said they would like more diversity in their midst. I affirm this hope, but I wonder if our understanding of what it means to welcome diversity is underdeveloped.

Was Adam and Eve’s ‘worldview’ the original sin?

Snowed in with my family over the Martin Luther King Jr. Day of Service, I stole a few moments away to read and reflect on racism in American society, how it persists even as its forms change, and ways to participate in its undoing. Like so many inspirational figures in human history, King’s message and memory have been grasped and used in numerous ways, toward many ends, by a fairly surprising variety of people. Everyone likes to have a little MLK in their pocket, to think of themselves as defending his legacy. But I must confess that my mind drifted from King toward another great American crafter of words and social critic, James Baldwin. Setting out to read his essay titled “Nothing Personal,” I found a particular thread tangling me up.

Who needs the church when we have the biblical worldview?

After his second visit to New York in 1939, Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrestled with the character of Protestant churches in America versus those in Europe in an essay titled “Protestantism without Reformation.” Even as he introduced his argument, which plays up history, sociology and political analysis for understanding the American church, Bonhoeffer offered some words of caution about using these modes. He expressed concern about balkanizing the global church, failing to see the single, shared office of God’s church in the world, and neglecting the real value of concrete church-communities that differ from our own. And I share these concerns.

Why your worldview might be both more and less than biblical

Today, I will work to read psychology and Christian ethics together to explore why it feels right to think of ourselves as common-sensical, biblical world-viewers — and how that self-conception misses the mark of the kind of creatures we are. Thus far in this series, I have largely analyzed worldview theory as it emerged in history. What follows has its historical elements but will begin to drive my criticism deeper into the posture and structure of “world-viewing” as it shapes our lives today. The worldview concept and its underlying impulse, as we already have seen, can allow troubling practices and convictions — biases, bigotry and otherwise bad ideas — to evade and even resist transformation in a Christian’s mind.

Putting the white in witness since the 1940s

Now is the time to bring our conversation about whiteness and world-viewing into the present tense. The language and concept of worldviews are somewhat clear in many corners of evangelicalism today, but how does whiteness figure into these concepts? And to what degree could this possibly be a problem among the everyday faithful? We may well acknowledge some of the historical problems (like Kuyper’s arguments around race and colony) without really thinking that the very form for thought established in those days could itself be a problem. Looking ahead, I acknowledge this is tough work, hard to do well in a short space, and requires good-faith effort from both writer and readers.

A short history of the roots of colonialism, racism and whiteness in ‘Christian worldview’

The state of the conversation around race in many corners of America, including too many churches, is a mess. And before we get too far down the road, I want to register my hesitation about trying to abridge what I argue with greater care and detail in my book. Wading into the borderlands of critical race studies is perilous, especially in a social climate where even the mention of terms such as “whiteness” is a nonstarter. My hope is to join or open a genuine, searching conversation, not shut down the very possibility. But I have seen enough to know how tough that needle is to thread — not least when one must start with an article title provocative enough to grab attention.

What if your ‘Christian worldview’ is based on some sinful ideas?

I suspect that few people who frame their ideas, or their disagreements with others, in terms of “worldviews” have felt the need to deliberate on what that word means, let alone whether it is valuable or valid. Few, that is, outside the evangelical circles that have labored to develop this sensibility in churches and schools over the last many years. This notion has a common-sense appeal and authority in 21st-century American life. Worldviews or world visions have become increasingly necessary in naming and talking about the many ways people see, reason about and live within our highly connected, densely diverse world.

Plan to Get Punched in the Mouth

When I see and hear pleas for justice, dignity or even mere recognition rising up against long odds, I empathize with the range of emotions that have broken through the surface tension of years past into a rolling boil. As a matter of personality, I tend toward anger, which partly explains why Christian ethics gripped me from the start. Given the nearly boundless opportunity I have enjoyed thus far in life, my anger around justice issues is mostly compassion – anger about the unjust, unfair, undue treatment of other persons and the inequities structured into human systems. All the same, my pendulum swings between two questions: What will I do about it? And how do I prevent this anger from eating me alive inside?

Review of David Crump’s I Pledge Allegiance

I Pledge Allegiance is a primer in the upside-down way of Jesus, addressed to his would-be disciples in 21st-century America who have divided their loyalties among other lords and “benefactors.” Throughout his book, David Crump juxtaposes an account of American evangelicals’ moral compromises when confusing their nation for the kingdom of God—support for civil authorities’ use of torture is Exhibit A—with a presentation of “ethics as if Jesus mattered” (to borrow a phrase from Glen Stassen). Crump provides not so much an introduction to Christian ethics “textbook” as a text tightly focused on the Jesus-follower’s essential mindset, which he fleshes out in later chapters on economics and the possibility of Christian military service. A driving question is: How does it look when a citizen of God’s kingdom maintains ultimate loyalty to Lord Jesus while living under earthly governance in a world beset with numerous malformative “discipleship” programs?